- Artists

- Agnès Vitani

- Anne-Laure Wuillai

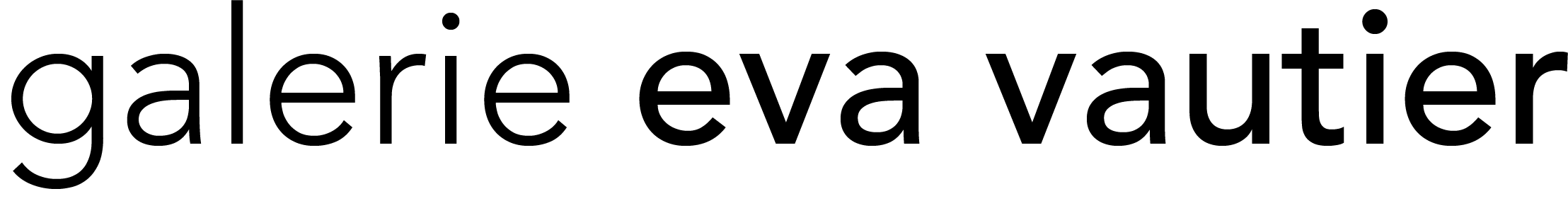

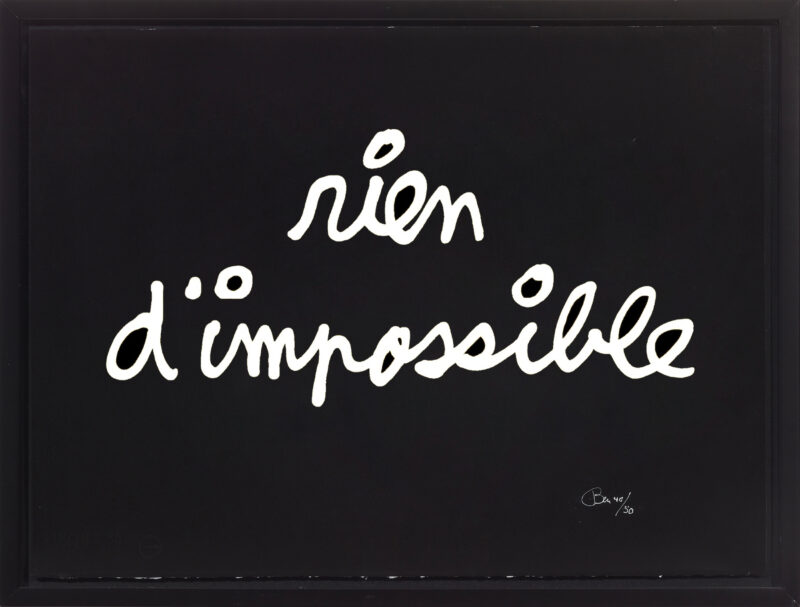

- BEN (Ben Vautier)

- Benoît Barbagli

- Marc Chevalier

- Caroline Rivalan

- Charlotte Pringuey-Cessac

- Florian Pugnaire

- Florian Schönerstedt

- François Paris

- Frédérique Nalbandian

- Gérald Panighi

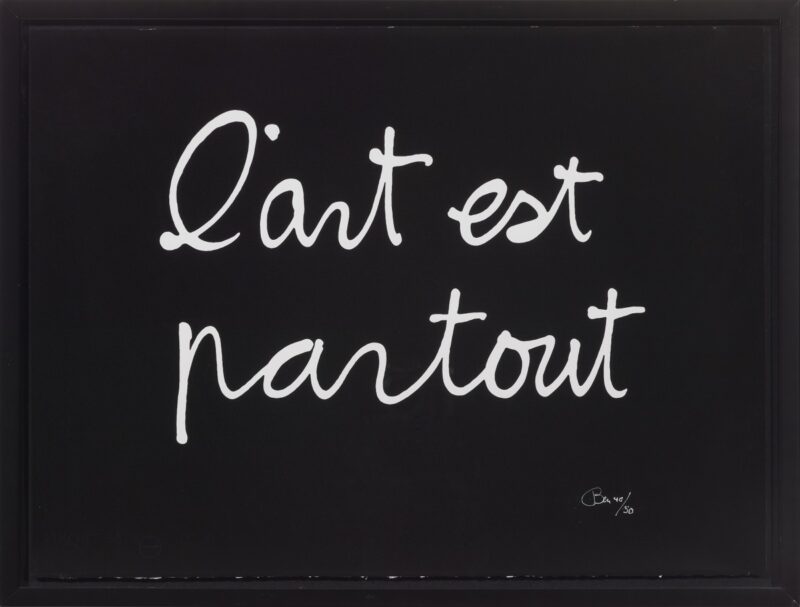

- Gilles Miquelis

- Gregory Forstner

- Jacqueline Gainon

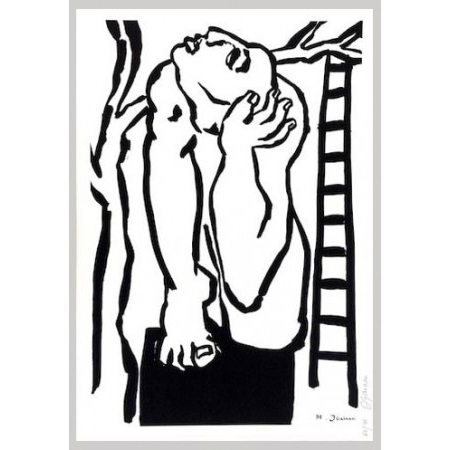

- Joseph Dadoune

- Jeanne Susplugas

- Maxime Parodi

- Mona Barbagli

- Natacha Lesueur

- Simone Simon

- Tom Barbagli

- Exhibitions

- News

- Store

- Eva Vautier Gallery

- Artists

- Agnès Vitani

- Anne-Laure Wuillai

- BEN (Ben Vautier)

- Benoît Barbagli

- Marc Chevalier

- Caroline Rivalan

- Charlotte Pringuey-Cessac

- Florian Pugnaire

- Florian Schönerstedt

- François Paris

- Frédérique Nalbandian

- Gérald Panighi

- Gilles Miquelis

- Gregory Forstner

- Jacqueline Gainon

- Joseph Dadoune

- Jeanne Susplugas

- Maxime Parodi

- Mona Barbagli

- Natacha Lesueur

- Simone Simon

- Tom Barbagli

- Exhibitions

- News

- Store

- Eva Vautier Gallery