[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” text_align=”left” background_animation=”none” css_animation=”” css=”.vc_custom_1411208040669{margin: 0px !important;}”][vc_column][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1586966165400{margin-right: 5% !important;margin-bottom: 200px !important;margin-left: 5% !important;}”]

September 27 to November 6, 2014

SO BE IT

Jacqueline Gainon and Frédérique Nalbandian

,

,

Jacqueline Gainon

,

Exhibition from September 26 to November 6

It is around the dilemma between image and painting, between memory and fantasy, between good manners and forbidden games that Jacqueline Gainon’s exhibition in the Eva Vautier Gallery is articulated. Placed under the sign of color, two series of large blue and red paintings confront each other in diametrically opposed registers.

Executed in an almost naive style, the blue series calls upon the artist’s childhood memories: it is based on a free interpretation of photographs of mountain excursions from a family album. The original images, taken by the artist’s father in the hinterland of Nice, are here the subject of a series of plastic operations. Their transposition into a monumental format, the passage from black and white to color and from the smooth rendering of photography to pictorial materiality gives them an undeniable sumptuousness. Finally, everything that was a landscape is replaced by a pastel blue background that reminds more of a child’s bedroom wallpaper than a summer sky. The picturesque elements still present in the first versions of the series – panoramas, rocky peaks or calvaries – have disappeared to make way for a space/time as abstract as it is timeless.

Between a pious image and a bad dream, these paintings show strange and incredibly peaceful portraits in which the artist, still a little girl, and the members of her family are standing against each other in a kind of half-sleep. Their eyes are closed and when they are opened, they seem to be definitively absent as if each one was looking inside himself ignoring the presence of the other. Sometimes their heads fall to the side or their faces fade away, while their bodies seem to float in this blue expanse. Their pallid complexion suggests the worst.

If the strangeness of the scene is due to this collective sleep, it is counterbalanced by the gestures of tenderness of this father and this mother towards their four children. There is something touching, still vibrant, which gives hope for a happy ending. The mind enjoys imagining this ideal family, alive and well, eyes open to the photographic lens because these images have something universal, they could be ours as well. But here the optics are replaced by the artist’s gaze, which clearly treats her childhood memories in a psychoanalytical manner as she displaces them. Thus, these snippets of the past reappear like moments lost forever, as if the artist could not restore the joyful temporality of his childhood but opposed an eternal rest. The opacity of painting with its lumpy and tormented materiality replaces the photographic evidence.

With tenderness and humor, Jacqueline Gainon distorts the idea of a family happiness that is all the more obsolete because it has gone to hell, thus affirming something of the order of disbelief in the family. Behind the initial naivety of these large icons, which are variations on the theme of the Virgin and Child, but which could also be compared to the popular practice of ex-votos by their deliberately clumsy side, there is an inexorable feeling of loss. No, painting is not a reassuring thing, it is harsh and impure. And isn’t the role of the artist to confuse and disturb? So be it.

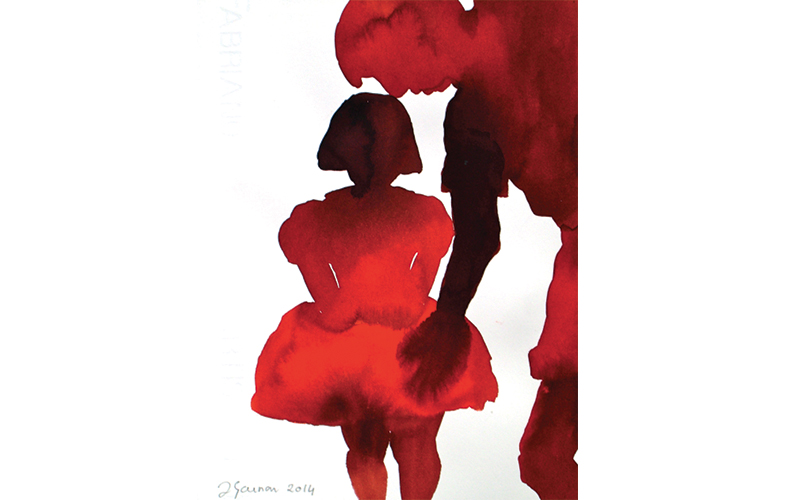

The red series is infinitely more gestural and expressionist. It obeys a very fluid pictorial treatment that leaves room for drips and colored juices. If the material is more transparent than in the blue series, this suite of paintings is also darker, literally and figuratively.

She stages a disturbing huis-clos in which a little girl dressed in a red dress becomes the prey of a group of young boys armed with bats and guns. We find the little girl who appeared in the images of the blue series with her 1950’s dress and who we suppose is the artist’s sister. But while in the previous series the child was as wise as a picture, here she is represented in movement, in perilous postures induced by the violence inflicted on her by her torturers. Blindfolded, she is tied up and beaten. Her little body struggles to stand upright as she is so badly beaten. She eventually fell to the ground.

It is difficult not to be touched by what is seen as a distant trauma, especially since the girl seems to be pushed out of the picture. If only we were given the opportunity to help him.

But who exactly are his assailants, who barely emerge from the shadows and whose silhouette seems to belong to the dark background of the paintings? Why are they attacking the girl? They look like members of an anonymous children’s militia. Their features are erased as if violence had no face. The eye, it is true, is entirely turned towards the red dress which twirls in the space of the painting and which ends up diverting our attention. One forgets that the boys are still in short pants and that their gestures, if one subjects them to a careful examination, are a little clumsy and borrowed. What if it’s just a game? Jacqueline Gainon sows doubt. So, secret militia or scouts?

We end up wondering if the object of desire of these young people is not also ours. It must be said that the artist has organized his compositions by dramatizing at will these scenes with their folded perspective and the plunging light that come to offer us on a tray the almost erotic body of this child with pink flesh all dressed in red. Here we are in the skin of the wolf. Between abuse and forbidden games, these nightmarish and suffocating scenes counteract the epinal imagery of the blue series and all the reassuring and ideal notions of family and especially of painting. They involve us in the erotic game of representation of which we become the voyeurs.

In addition to this very intense pictorial series, there are extraordinary small drawings in Indian ink and gouache felt-tip pen where the battle seems to be rebalanced in places. Sometimes the girl manages to keep her attackers at bay. The victim becomes the executioner, to the delight of the viewers. Finally, Little Red Riding Hood in her light dress that we would like to see made of muslin climbs on a huge skull where she manages to balance herself, thus making a mockery of death. So be it.

Catherine Macchi

Untitled, 2014, Oil on canvas, 146 x 114 cm

Frédérique Nalbandian

,

Frédérique Nalbandian is a graduate of the International Pilot School of Arts and Research, Villa Arson, Nice. Since these years spent experimenting with forms in the making, she has refined her material science and her interest in the vast and troubling question of the passage of time. Soap still plays a major role in her work as a sculptor, but also plaster and glass. Depending on the occasion, these substances are loaded with water, air, carmine red pigment and charcoal powder, and are impregnated and even bruised. Chemical exchanges take place in installations that follow the laws of uncultivated landscapes or dialogue with architectural spaces charged with meaning. In these works from which emerge as many volumes in balance as “untouched” structures, the artist declines motifs such as the circle and the column. In other works that say something about man’s relationship to the world, it is a question of the ear and the understanding, of praying hands and near-silence. Here, receptacles with their large surfaces of vibrations, there, concretions made of folds and meanders like those of the brain for example. Undeniably, these works, by their repetitive force and their power of integration of linguistic signs – one must listen to the titles that the artist attributes to his works -, impose the idea of a quest based on the poetic and haunted by what makes the prodigy of it: the blossoming of the sense, its possible dehiscence, without the recourse to the argumentation or to the least dialectical system. Finally, it must be said that Frédérique Nalbandian executes a number of drawings where a weaving of references to art history and imprecise anatomy emerges with more or less clarity on the paper. A partition, one could say, between what would come from the desire to describe the whirling of the sky and that of putting the man at the center of the system…

Text by Ondine Bréaud-Holland

Trips, Carros 6-01-13, Nice 01-09-14, 2012 2014

soap, marble, evolving piece

200 x 64 x 42 cm

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]