[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” text_align=”left” background_animation=”none” css_animation=”” css=”.vc_custom_1480929048079{margin-right: 150px !important;margin-left: 150px !important;}”][vc_column][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1487341453287{margin-top: 50px !important;margin-right: 150px !important;margin-left: 150px !important;}”]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” text_align=”left” background_animation=”none” css_animation=””][vc_column css=”.vc_custom_1475980873284{margin-right: 100px !important;margin-left: 100px !important;}”][vc_column_text]MECHANICAL STRESS, Pauline THYSS

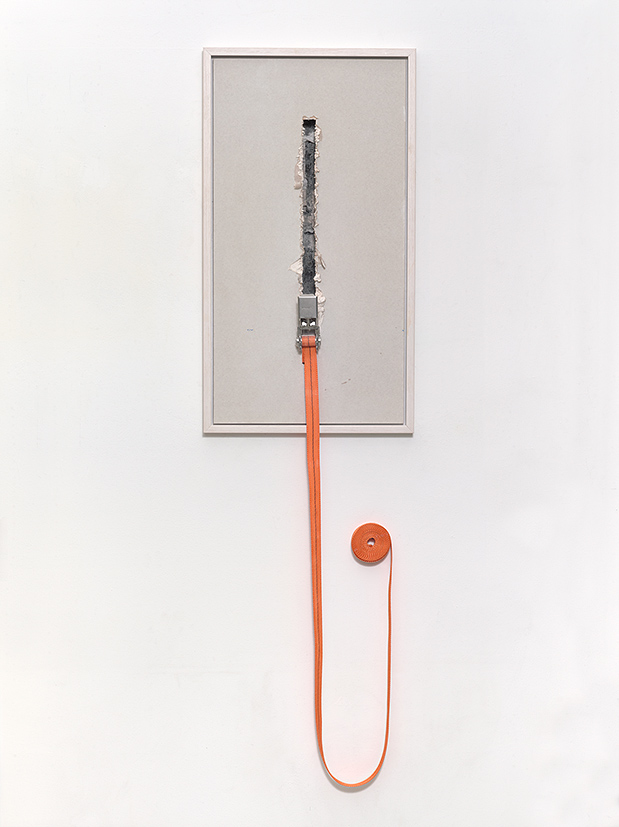

“MECHANICAL STRESS” Florian Pugnaire

September 24 to December 30, 2016

From mechanical constraint to the narrativity of gesture

Using materials traditionally used in construction (plasterboard, sheet metal, lead), he is interested in their physical properties, their resilience, their remanence … which is measured through mechanical stress, or mechanical stress. This concept, used in materials science, evaluates the elastic and plastic capacity of an element to absorb torsion, tension or pressure effects. Florian Pugnaire relies on certain specificities – the flexibility of lead, the resistance of metal, the fragility of plasterboard – to which he imposes a working force that can sometimes bring the materials to their breaking point. To do this, the artist uses mechanical tools such as straps, winches, hoists and hydraulic cylinders that are sometimes an integral part of the work. This tool is diverted from its ordinary application to operate constraints and deformations, creating a plastic vocabulary whose industrial aesthetics, here tormented, tends towards the collapse, the ruin, the degradation…

Florian Pugnaire’s works would be the remnants of the fight he leads with the material, because he considers the studio as the place where he practices the battle of art: he confronts the elements in a fight where each round tests their respective physical capacities. His approach to sculpture is therefore fundamentally defined by a performative dimension, characterized by the action and involvement of the body. In this, his sculptures are haptic works: touch and self-perception in the environment are central to his process. If in his duo practice with David Raffini, he explores the sculptural field via monumental installations or “event-works”, he produces individually works on a more human scale. The question of the process is however at the center of these two practices, which we could call action-sculpture ¹: just as inaction-painting, the gesture is here more important than the result.

There is a form of indeterminacy in his practice since experience directs the process: his sculptures are both reproducible (once their manufacturing process is established) and singular, since they are each time the result of a unique action. In this perspective, the practice of Florian Pugnaire is in line with the theory of the Anti-form ² defended by Robert Morris and gathering artists like Eva Hesse, Bruce Nauman or Barry Flanagan: to produce his works, he does not look for a precise figure but finds his form by manipulating the material. Formal similarities with the work of Eva Hesse are also sometimes obvious: her metal sheets constrained by a metal frame(Untitled, 2016) echo Aught (1968), a piece composed of plastic sheeting held to the wall by a tape frame. But his combative approach to the process distances him from the gentle works ofAnti-form : his sculptures are dynamic, visually sometimes violent, even violent.

Florian Pugnaire thus proposes formal potentialities more than determined forms: he freezes the material in a given state at a moment “T”, empirical and decisive. This process produces freeze-frames that generate recognizable shapes (a punching bag, a flag) or snapshots (folding, twisting, compression). For example, his series of lead sculptures (2016): the artist uses the same amount of material-sheets measuring 60 x 90 x 0.1 cm-that he works into five variations. A dense, twisting knot gradually unfolds to become an aerial drape, seeming to float lightly. The form thus evolves from a simple gesture, the maximum twist of a leaf (the knot) to the creation of an image, an erected flag. The deconstruction of the movement, almost chronophotographic, produces here visually the idea of a duration. A kind of timeline with different formal potentialities, it produces a plastic narrative, a silent narration. It refers us to a history of the sculptural gesture, from the classical drape to Richard Serra’s Hand Catching Lead (1968).

In other works, this narrativity is rather suggested, but the form always contains an analepse (or flash-forward) in its movement: the base of Constriction (2016) is potentially totally destroyed, the sheet metal of Crossing (2016) could go completely through the wall, the punching bag of Untitled (2016) to be no more than a shapeless mass… In other words, the form always contains the anticipation of its total and irreversible destruction. This temporality is thus based on the entropy of the material, which naturally tends towards a state of disorganization, and on the gesture, thanks to which the artist maintains this disposition to chaos in a transitory state.

On the other hand, this plastic narrative contains two forms of prolepse (or flashback). A historical memory that translates into artistic references that are sometimes antagonistic (Greek sculpture meets minimalism, the ready-made plays with processual art…) and a much more specific reminiscence, that of the time of elaboration. This past, usually invisible in a finished work, indirectly refers us to the space of the studio and the innumerable potentialities of a work in the making: “I pay particular attention to the notion of the studio as a place of practice, but also as a place of fiction, an in-between where the finality of the work is not yet definie and where everything can still be invented or modified.³”

The fictionalization of the process: video and cinema

Since his third year of study at the Villa Arson, Florian Pugnaire has documented his gestures in the form of films. At first thought of as archives, these videos quickly freed themselves from this status to become works in their own right. The influence of Bruce Nauman was then important, in particular his videos of the end of the Sixties in which the artist puts himself in scene in the workshop, executing a simple and repetitive gesture (to walk, to hold in balance on a foot, to bounce on a wall?) These elementary gestures experimented with in the form of filmed actions, not without links to the activity of dancers such as Merce Cunningham and Trisha Brown or Brecht’s theater, allow Nauman to test modalities: those of the body intervening in time and space, those of the limits of relevance of an action, even those of the body as the primary material of the work.

His first video was intended to document the making of a sculpture: in Dialogue with Sculpture (2004), we see him punching a punching bag made of aluminum sheet for three minutes. Aware of the performative dimension of his action, he filmed himself from three different angles in order to obtain a complete vision. He says, “It was in importing the media from the three tapes that I realized the impact of the editing: my three cameras were not only around the object, but framed three different shot values, which, with the right rhythm, gave a dynamic look to the action. While my intention was to make a sculpture in a performative way and to document the process, I realized that the archive I had produced was an integral part of the work in its entirety.4 ” From this initial desire to bear witness, therefore, a reflection on the video medium itself ensued, leading the artist to think of it in terms of its own characteristics; over time, the shooting, framing, color grading, sound and editing of his films have been perfected and now give his works a truly cinematic dimension.

The issues he addresses in his videos are the same as in sculpture: he questions the processes of making the work by staging constraints, transformations, destructions … We find an aesthetic of the site and the workshop and a same plastic vocabulary (metal, plaster, hoists, straps …). But, by revealing the processual phase in time and not only in space, Florian Pugnaire transforms it into a fictional experience. Here, the narrativity of the work does not rest only on the entropy of the material and on the gesture since the image in movement induces a temporality per se. Often accompanied by installations from the film set, his videos question in a complex way the creative time by distorting it: analepses and prolepses overlap, blurring the linearity of the narrative; the work is continuously renewed between construction, destruction and reconstitution.

If in his first video works, he tries to archive the activation of a processual sculpture, Florian Pugnaire quickly autonomizes the gesture to produce movements seemingly induced by the process itself, without human intervention. Taking place in indeterminate spaces, between the wasteland, the workshop and the white cube, his videos unfold the processual gesture to create chain reactions: the decor self-destructs and the materials become actors of spectacular pyrotechnic and mechanical catastrophes. And when the body comes back into play, as in Stunt Lab (2009) or Agôn (2016), it seems to undergo this same extraordinary force: the gestures are destructive and the organisms are as abused as the materials that surround them. While watching his films, we think of Der Lauf der Dinge (The course of things(1987) by Peter Fischli and David Weiss, in Water Boots (1986) by Roman Signer or One Minute Sculptures (1997-1998) by Erwin Wurm: provisional sculptures, resting on a precarious balance, leaving in suspense or activating an imminent and programmed catastrophe, they put back into play, with a derisory dramatic intensity, the fundamentals of the sculptural practice as a determined and immobile form

But Florian Pugnaire’s films carry a gravity that is foreign to these works: shrouded in a strange, sometimes nightmarish atmosphere, they take us back to fantasy films. In Paramnésis (2011), we observe a succession of events unfolding through different spaces, initially immaculate and circumscribed, then increasingly dirty and indeterminate. Several mechanical reactions take place: impacts, flows, absorptions. The atmosphere becomes unhealthy, disturbing: acetone flows over polystyrene, which melts to create blackish threads, evoking Alien (1979) by Ridley Scott; a metal sheet sinks into a wall to leave a gaping hole, black as nothingness… “In space, no one will hear you scream”, seems to tell us these poor tortured materials. In space, no one will hear you scream,” these poor tortured materials seem to tell us.

The works he creates with David Raffini have something more romantic about them. Their videos, whose main characters are usually vehicles (backhoe, van, car) are the subjects of a poetics of metamorphosis, leading processual fiction to phantasmagoria. From these videos came sculptures made from these machines: playing with an ellipse between cinematographic time and reality, these often violent works – the backhoe of In Fine folds in on itself, theDark Energy is dismembered – send us back to the fiction of their making. The filmed account of their metamorphosis is both real (the effects are mechanical and not digital) and mythical: we travel with them through wastelands and abandoned plains, we sympathize with the inescapable transformations they undergo and end up giving them an anthropomorphic and ontological dimension. “In Dark Energy, or in In Fine, mechanical devices are shown both as “utilitarian” and fantastically glorified, human and extra-human. (…) Thus, these mechanical machines are associated with the idea of quasi-mythical ancestrality at the same time as they are metaphorical of the ” homo faber “This definition of man as forever agitated, forever caught up in the desire to make – and consequently to transform – his environment.5 “We then think of Christinea book by Stephen King published in 1983 and adapted by John Carpenter the same year, or to Crash! by Ballard (1973), adapted by David Cronenberg in 1996: the machine becomes mortal, elevated to a symbol of the human condition and a vector of our own loss.

Agôn (2016) would be the sum of all these reflections and it is the most syncretic work of Florian Pugnaire. We see two fighters confronting each other, trapped in an atemporal loop. The set comes to life and metamorphoses around them to finally self-destruct: carried away in this perpetually mutating scenography, the actors seem absorbed by the violence of their own action, almost indifferent to the brutal reactions that surround them.

Here again, Florian Pugnaire speaks to us of process and Agôn is certainly a film of sculpture; however, it is also a truly cinematic work. The narrative thread is based on a chain reaction leading us into a succession of spaces in which the fight unfolds. The editing alternates between close-ups of the action of the two protagonists and elliptical shots revealing the extent of the setting, creating dynamic variations in rhythm. The sound brings a fantastic atmosphere while rendering the realistic aspect of the fight. Close to the bodies, he focuses on the impacts and the rush of breath while evolving according to the changes of space, recalling at times the disturbing Polymorphia (1961) by Krzysztof Penderecki, used by William Friedkin in The Exorcist (1973) and by Stanley Kubrick in The Shining (1980). This anxious atmosphere is grafted onto the aesthetics of the studio: the construction and deconstruction of the set bears witness to a process involving the making, the unmaking, the gesture, the gestation, the sculpture in the making.

Produced with the professional techniques of the film industry, Agôn is therefore an art video in which cinema is both integrated as a reference and as a form. Florian Pugnaire’s influences are varied but all belong to the genre cinema: martial arts films (from Akira Kurosawa’s Chanbara to John Woo’s Hong Kong cinema), fantasy and science fiction cinema (Tobe Hooper, David Cronenberg, Stanley Kubrick)… By relying on this repertoire, the artist allows himself an incursion into entertainment, leading his aesthetic problems towards the spectacular. We are indeed amazed and we leave the screening fantasizing about an improbable remake of Fischli & Weiss’ The Course of Things by John Carpenter.

However, Agôn has nothing to do with Hollywood productions: for Florian Pugnaire, artistic fiction must understand the way the image industry generates codes of representation in order to divert them and create alternative forms. “Since Greenberg, the flow of globalized images, the exploits posted online, the endless replicas ofentertainment productions have been rushing into our reception channels. Play and fiction are now included in the self-reflection of art. And unlike entertainment, artistic fiction does not aim to hypnotize the spectator, even if it would let him absorb his content.6 ” In AgônThe spectacular plays with the spectacle, the artifice is thwarted by the real and performative staging of the action, and the violence poses an axis of reflection on human nature.

For if Florian Pugnaire uses certain mechanisms of Hollywood cinema, he rejects the Manichean vision. The combat, like the term Agôn and its polysemy 7, proposes several ways of reading. From a narrative point of view, it is absurd: we will never know why these two adversaries are so keen to annihilate each other and we will never know their history. The absence of context transforms the filmic experience into a powerful visual and sensory exploration that imprints itself on our retinas and stays with us for a long time. The atmosphere, all ruins and mists, reminds us at times of the Zone of Stalker (1980, Tarkovski): the physical space becomes mental and the fight is tinged with an ontological, even metaphysical dimension. Between the instincts of life and death, Agôn reminds us of the vanity of our existence and our irrational and essential will to overcome it.

As Kubrick said: “A film is – or should be – much closer to music than to a novel. It must be a sequence of feelings and atmospheres. The theme and all that is behind the emotions it carries, the meaning of the work, all that must come later. You leave the theater and, perhaps the next day, perhaps a week later, perhaps without your realizing it, you acquire something that is what the filmmaker has been trying to tell you.8 ”

Pauline THYSS, September 2016

[1] Claire Moulène, in the article Action Sculpture published in Code 2.0 in the fall of 2010, defines the practice of Florian Pugnaire and David Raffini as follows.

[2] Article published in Artforum (VI, n° 8) in April 1968 in which Robert Morris, opposing minimalism, defends a process according to which the artist delegates the artistic choice and the gesture to the material. This article lists, since Jackson Pollock and Morris Louis, the American expressions of this process which “lets speak” the matter, the gravity and the chance.

[3] Florian Pugnaire, about Stunt Lab, 2010

[4] Interview, Pauline Thyss and Florian Pugnaire, 2016

[5] Sylvie Coëllier, Dark Energy: Chronicle of an Announced End, in catalog Dark Energy, Pablo Picasso National Museum, 2014

[6] Sylvie Coëllier, Pugnaces et raffinés – Florian Pugnaire et David Raffini : une épopée des moteurs, 2013.

[7] The genealogy of the term Agôn goes back to the texts of ancient Greece and reveals, since its origin, numerous shifts of meaning. It appears in the Iliad, to describe the assembly witnessing the establishment of the funeral games, before evolving in the Odyssey to designate the arena in which the tournaments take place. He then goes on to define the Panhellenic games, and then some of their specificities linked to the notion of combat, such as competition, struggle, and rivalry. Finally, Agôn can designate the place of the fight as well as the fight itself, the combativeness and, by extension, the judicial or verbal joust, the dialectical debate, the theatrical dispute…

[8] Stanley Kubrick’s words collected by Peter Lyon for Holiday magazine (February 1964)

[/vc_column_text][vc_tta_section title=”Exhibition visuals” tab_id=”1475979861305-84abfddb-5660″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_tta_section][/vc_column][/vc_row]